Behind the Statistics: Power Asymmetry in the Urban Regions

This blog is inspired by a figure (see Figure 1) that I came across when reading Thompson et al (2000)'s research about the changes in urban water use in East Africa between 1967 and 1997.

Overall, the mean per capita water use in urban areas in East Africa decreased over the three decades. The water use from piped water sources also decreased. However, the usage of unpiped water resources increased. Mathematically, the compound annual annual growth rate (CAGR) of the unpiped water resource is 1.53% and -2.18% for piped water resources. It means that every year people would reduce their piped water usage by 2.18% as compared to last year and increase their water usage from unpiped resources by 1.53%.

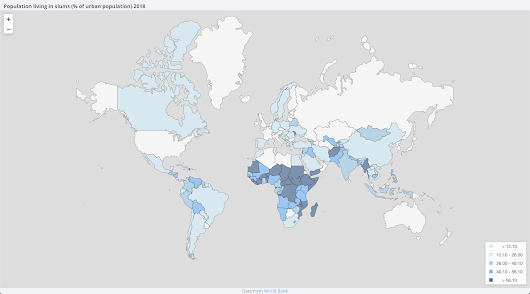

Now, let's think about what else had happened during that period. Africa went through an accelerating urbanisation process. Maps produced by OECD (see Figure 2) show that in 1970, there were only 4 countries that have 33-49 share of the urban population, no country has more than 66% urban population. However, just over two decades, the number of countries that have 33-49 share of urban population climbed to 13, two countries appeared in the 66-79 share of urban population category, and one country reached over 79% urban population. These indicate a massive inflow of migrants in the urban regions throughout the continent. Then, we all know the rest of the story.

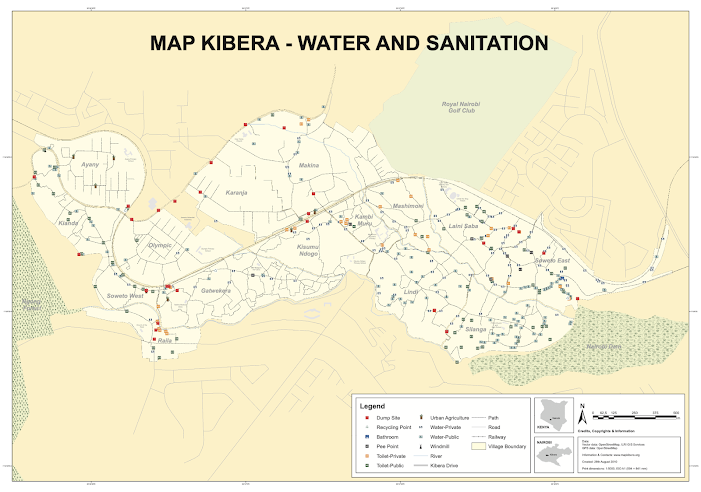

Another set of statistics (see Figure 4) provided by the United Nations shows that the proportion of the population with an improved drinking water supply and access to sanitation facilities in Africa decreased from 57 to 54 over two decades whereas there was an improvement in rural regions. Just as Joan Clos, the executive director of UN-Habitat pointed out,

"Africa is the fastest urbanising continent on the planet and the demand of water and sanitation is outstripping supply in cities."

Your take on explaining water and sanitation issues through statistics is really powerful in addressing the sanitation issues in Africa. Your example of Lilongwe reinforced the inequalities that are present when receiving water and therefore further emphasises that the water and sanitation problem is not clear cut and these inequalities need to be thought about (well done! :)). This blog post was very well thought out and unique as you tied urbanisation and its link to the sanitation and water issues together.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much!

DeleteA thoughtful and well-argued post!

ReplyDeletethank you so much!

Delete